Features

Meeting halfway

How San Jose State University students can compromise the sobriety of those integrating back into society.

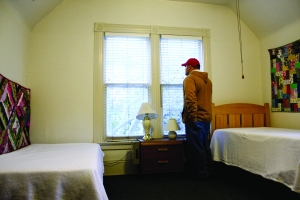

George Padilla, Stevens House manager, stares out the window of the house’s empty room from which SJSU’s Joe West building can be seen. The Stevens House currently only has five of seven residents.

Upon arriving at SJSU, I was quickly introduced to the term “halfway house.” My peers seemed concerned about these homes being close to school, although no one actually knew much information about what went on inside of them or why they were, if in fact, dangerous. Words such as unsafe, homeless and pepper spray were used in most descriptions.

Initially, whenever I passed by the last house on my block, I found my feelings of normalcy displaced. The city’s symphony muted at this corner house. A peculiar group was visible there, leisurely sitting on their house’s wraparound porch. Day in and day out, the residents can be found, just sitting and staring, not muttering more than a word. It was unknown to me how these houses and their residents came to be and where they fit in downtown.

Later, in my short-lived experience in the Greek system, I learned that many halfway homes were located on fraternity row, and no one seemed too delighted about it. I could not help but wonder why my porch-sitting neighbors had such a bad reputation among students.

Early one evening I found myself in front of the Stevens house, a light-yellow Victorian with a doormat that greeted me, “Welcome.” I rang the doorbell and seconds later an older man opened the door. “Hi. George?” I asked.

“George?” Appearing confused, he backed up a few steps allowing me to peek inside.

“Hi. I’m George.” Alas, the real George Padilla walked to the front door and shook my hand. He was, what seemed to me, a 27-year-old Santa Clara University student and the on-site representative at the Stevens House. “Jim this is our guest Calli,” he said.

With little emotion, Jim shook my hand and returned to the living room where he was watching “Friends.” His hair was white and his teeth have yellowed. He apathetically stared at the television set, reminding me of my corner neighbors sitting on their porch. It was clear that although he might have been a little odd and lacked some personal hygiene, he was harmless.

The house was quiet and clean, much like a bed and breakfast. A guest sign-in book sat on a table in the foyer of the house. Above, there is a modest shrine to Roy Stevens, the volunteer whom the house is named after.

“Here, I’ll give you a tour.” George began to show me around. Everything was strikingly normal from the standard kitchen to the bland beige walls. He led me into the backyard, a serene setting with a hammock and garden. Another resident joined us outside.

“Charles, this is Calli.” Charles was different from Jim. He was younger and he did not fit my perceptions of someone with disabilities. “Hi.” He threw up his hand and shot me a stern look. He then walked right past me to sit on a patio chair and lit up a cigarette. George and I continued our conversation.

“This is the barbecue,” he said. He seemed tense. I looked to Charles, who was staring at us, appearing amused at George’s discomfort. George looked back at Charles and eased up, continuing to tell me about the potlucks and barbecues he puts on at the Stevens house. “Members from the church next door come over and bring food for barbecues.” Charles was still staring. He then plotted his lit cigarette into the ashtray on the patio table and walked over to the garden where he picked up the hose.

“We got a new hose?” Charles interrupted. “Yeah, I guess we did?” George responded, puzzled at Charles’ question. Charles stood with the green garden hose in his hand. Sensing my discomfort, George led me past Charles, still with the hose in his hand, inside. George informed me that Charles is bipolar, as well as very bright, and has been living in the house the longest.

James Kudelka, 66, watches his favorite television show in the Stevens House’s living room. The Stevens House is named after Roy Stevens, who dedicated 15 years of his life to advocating for the homeless of San Jose.

Throughout the tour, I learned that the Stevens House is a transitional housing project of the nonprofit organization, Innvision. Seven formerly homeless individuals who have been diagnosed with mental illnesses reside there, some of which have a history of drug use or other crimes. The residents have been handpicked from emergency shelters. They are allowed and encouraged to stay for up to two years, during which they must maintain a sober lifestyle, do weekly chores and pay a rent of $250 a month, which they collect from social security. The ultimate goal is for them to, in a sense, graduate and move into more permanent housing.

We headed upstairs and on the way we passed Jim again, still staring at the television. “Jim, would you mind if I show our guest your bedroom?”

“Sure.” He replied, his eyes glued to the TV.

George has authority to walk into Jim’s room without permission — in fact, it’s part of his job. “I want them to get a feeling for what it’s like to have their own home. On the streets, no one tells you what to do. That is why I ask him for permission.”

“What made you so interested in halfway houses?” he asked me. As I explained to him the halfway houses’ bad reputation amongst students, he seemed shocked.

“I don’t understand why,” he said. I was beginning to think the same thing.

Upstairs, he led me into a vacant bedroom overlooking 10th Street. I looked out the window at the cars and people whipping by, and as I stared, I begin to feel like my neighbors on the porch. I remembered my weekend nights in San Jose over the past two years. How many times had I and other students walked down the street below to various parties?

“Do you think halfway houses being located so close to campus are dangerous for students?” I asked. “Or do you think students are more harmful to your residents?”

He looked surprised at my question. “It’s interesting that you bring that up. Right now you hear cars and students walking, but at night, it changes from traffic to voices. They are loud and it becomes clear that they are intoxicated. It’s difficult when you have people trying to live in a sober environment.”

“Have you ever had problems between the students and your residents?”

“No.” he responded. “You see, unless they are in the backyard, which would be a completely different situation, they are not outside. You would never see one of our residents outside bothering anyone on the street. It wouldn’t happen because I would not allow it. It is my job.”

It became clear to me that the halfway houses are not harming students. On the contrary, our college lifestyles are actually taking a toll on their recovery. Thinking of the partying that goes on, it must be hard to live there and be a recovering drug addict, not to mention mental illness. If halfway house residents can tolerate students, why do some students seem to have such a lack of tolerance toward them?

Kudelka watches television, while Kenneth Jiles, 50, the newest Stevens House resident, calls his family to remind them to wish his son a happy birthday.

“How many people make it through the program?” I asked. “In the four years I’ve been here, there have been 25 different residents and I would say that I think only about two have successfully moved on with their lives,” he said. I could tell that it was disheartening for him.

He put out his two hands and cupped them in front of him. “I mean, here is what we can offer you.” He looked at his hands. “It’s not much, but it’s here for the taking. It’s here for you and that’s all that I can really do.” Even though George is in charge of watching the residents, he cannot help but develop friendships.

He got up and led me into another room. “This is Charles’ room.” He picked a candy wrapper out of the trash can. “Here’s a sign of Charles defying my authority. Charles has been here the longest and he is very intelligent, so obviously Charles and I have gotten to know each other the most,” he said. Charles has a laptop, a new desktop computer and subscribes to Netflix. “He wanted to buy Comcast cable in here and he just purchased a van,” he said.

“And that’s bad?” I asked.

“Charles’ two years is up in a few months and he hasn’t shown any desire to save money. These are all signs that lead me to believe that Charles is planning on moving into his van after here.” Charles will probably end up back on the streets. I began to understand how difficult George’s job can be.

“Does it hurt your feelings?” I asked.

“Honestly, yes. It is almost like a slap in the face.” I became unsure if I could take on George’s job. Sure, he is changing people’s lives, but at the end of the day people have to want help to change. Halfway houses do not create problems. Rather, they create solutions. They provide assistance to people who are trying to turn their lives around and become functioning members of our community.

I walked back home that night and turned onto my street. The corner house had gone dark and by now the residents were all inside eating dinner, watching television and coping with disabilities and addictions. People, me included, often have ill-informed ideas about halfway house residents, but as I looked up at my neighbors that night and thought about my experience, I began to understand them and moved past my preconceptions.

Sidebar –

How do students feel about halfway houses?

“How do you feel about halfway houses being located so close to campus and your home?”

Student Responses:

“I think that students like myself know that the houses are there, but we don’t really know about them. So I don’t really know whether to feel safe despite them being there or if I should

be worried about the sort of people being housed so close to students.”

– Jenna Cabral, SJSU student, resides six houses down from a halfway house

“I don’t think that they should be close to a college campus. I think that a more segregated area would be a better fit for such a house. It’s not too safe either for students.”

– Nick Cukar, SJSU student and athlete, resides two houses down from a halfway house

“I think they’re a positive thing. I’ve never been affected by them in a negative way.”

– Patrick Radford, SJCC student, resides two blocks from a halfway house.

Callie Perez

Latest Comments